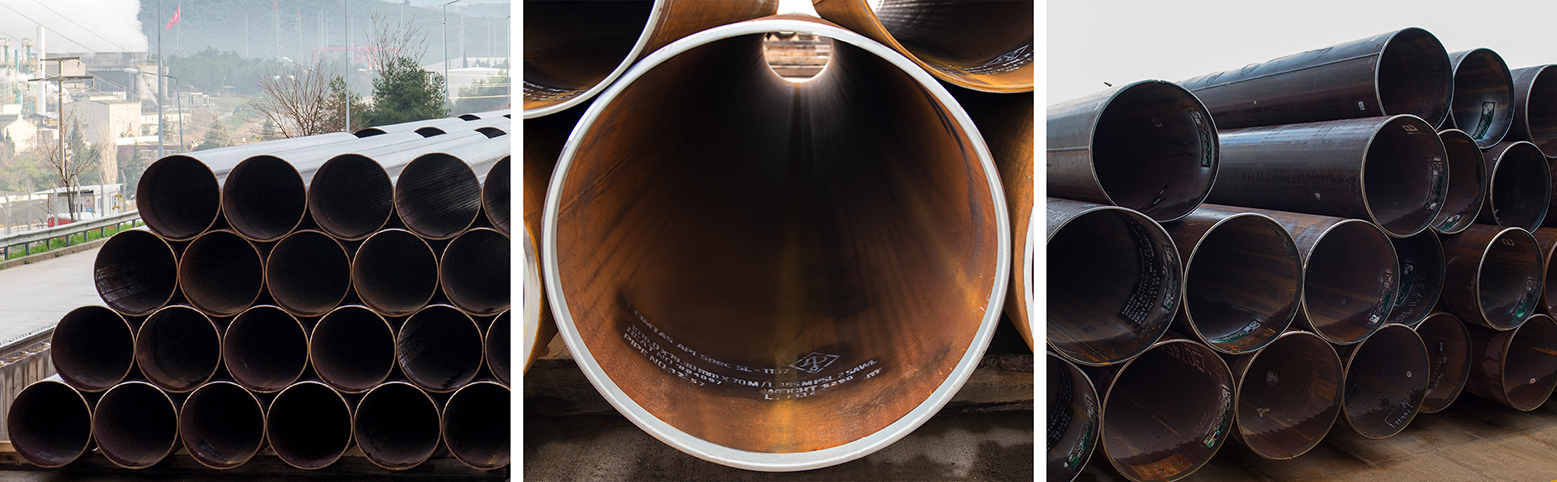

EN 10219 Structural Steel Pipe – S235JR S355JR S355J0H S355J2H

The Foundational Principles of EN 10219 Structural Steel: A Metallurgical and Standardization Framework

Structural steel, at its core, represents a carefully balanced alloy of iron and carbon, fundamentally designed to provide high strength and rigidity at the lowest possible cost, forming the skeletal backbone of modern infrastructure. The EN 10219 standard, specifically titled “Cold formed welded structural hollow sections of non-alloy and fine grain steels,” provides the rigorous technical framework within the European Union (EU) for the manufacture and supply of steel pipes and hollow sections used in general construction and civil engineering. It is distinct from EN 10210, which covers hot-formed sections, and this differentiation is crucial because the cold-forming process intrinsically influences the material’s final state, mechanical properties, and inherent residual stresses, necessitating specific compositional and testing requirements.

The grading system employed by EN 10219 is systematic and informative, offering an immediate insight into the material’s key characteristics. The prefix ‘S’ stands for structural steel, universally indicating its intended use. This is followed by a number—235 or 355—which defines the minimum guaranteed Yield Strength ($\text{R}_\text{eH}$) in Newtons per square millimeter ($\text{N}/\text{mm}^2$ or $\text{MPa}$) for the base thickness range (specifically, up to $16\text{mm}$ thickness). This numerical designation is the most crucial piece of information for the structural engineer, as it directly governs design calculations, section sizing, and load-bearing capacity. The subsequent letters and numbers, such as ‘JR’, ‘J0’, and ‘J2’, relate to the guaranteed Impact Energy—the material’s resistance to brittle fracture—at specific sub-zero temperatures, reflecting its suitability for colder climates or dynamic load applications. The letter ‘J’ signifies a minimum impact energy of $27\text{J}$ (Joules), while the appended characters denote the temperature at which this energy must be achieved: ‘R’ indicates testing at room temperature ($+20^\circ\text{C}$), ‘0’ indicates testing at $0^\circ\text{C}$, and ‘2’ indicates testing at $-20^\circ\text{C}$. This systematic nomenclature ensures that an engineer can quickly select a material with the necessary combination of strength and toughness for a specific operational environment, mitigating the risk of sudden, catastrophic brittle failure, which is a major concern in steel structures subjected to high strain rates, sharp notches, or low ambient temperatures.

The final element, ‘H’, which is specifically applied to the $\text{S355}$ grades under discussion (S355J0H and S355J2H), signifies that the product is a Hollow Section, confirming its direct applicability under the EN 10219 scope. This holistic naming convention—combining strength, toughness, and form—is a cornerstone of European material specification, allowing for highly efficient and standardized material selection across the continent. The fundamental difference between the S235 grades and the S355 grades lies in their alloying and rolling processes. S235 is the basic, unalloyed structural steel, relying primarily on its low carbon content and standard rolling techniques. S355, conversely, achieves its significantly higher yield strength through more deliberate alloying additions (primarily Manganese ($\text{Mn}$)) and often through controlled rolling or micro-alloying (using elements like Niobium ($\text{Nb}$), Vanadium ($\text{V}$), and Titanium ($\text{Ti}$)) to refine the grain structure and enhance strength via precipitation hardening, a technique known as Thermomechanical Controlled Processing (TMCP), which is crucial for balancing weldability and strength.

The Chemical Blueprint: Controlling Strength and Weldability Through Composition

The chemical composition of structural steels conforming to EN 10219 is fundamentally a compromise between achieving the required mechanical strength and maintaining excellent weldability. Unlike specialty alloys where high strength is paramount and cost/weldability are secondary, the large-volume structural steel market demands ease of fabrication in the field. This necessitates strict control over elements that significantly influence the steel’s hardenability and the potential for cold cracking in the Heat-Affected Zone ($\text{HAZ}$) during welding.

The most critical element to control is Carbon ($\text{C}$). While carbon is the primary strengthening agent in iron, increasing its content rapidly degrades weldability and increases the steel’s tendency towards brittle behavior. For the higher strength $\text{S355}$ grades, the maximum carbon content is significantly restricted compared to older standards, reflecting a modern preference for achieving strength through non-carbon alloying and microstructural refinement (TMCP). The standard achieves this weldability assurance not just through direct elemental limits but also through the calculation of the Carbon Equivalent Value ($\text{CEV}$). The $\text{CEV}$ is an empirical formula used to quantify the combined effect of all alloying elements on the material’s hardenability, providing a single metric to predict the susceptibility to cold cracking during welding. The most common formula used for the EN series steels is the International Institute of Welding ($\text{IIW}$) formula:

The EN 10219 standard places specific maximum limits on the $\text{CEV}$ for each grade, especially for thicker sections. By limiting $\text{CEV}$, the standard inherently dictates that fabricators can utilize standard, high-productivity welding procedures with minimal or no preheating, a major economic and logistical advantage in construction projects.

Manganese ($\text{Mn}$) is the second most critical element. It is a powerful strengthener that works synergistically with carbon, but more importantly, it promotes the formation of desirable fine-grained pearlite structure and is key to improving both hot workability and impact toughness. The higher strength $\text{S355}$ grades invariably have a higher $\text{Mn}$ content than the $\text{S235}$ grades. Other minor elements like Phosphorus ($\text{P}$) and Sulfur ($\text{S}$) are strictly limited, as both are detrimental; $\text{P}$ reduces low-temperature ductility, while $\text{S}$ forms $\text{MnS}$ inclusions, which severely degrade impact toughness, particularly in the through-thickness direction, an important factor for tubular connections. The lower $\text{S}$ and $\text{P}$ limits in the $\text{J0}$ and $\text{J2}$ grades reflect the increased demand for guaranteed low-temperature toughness.

Table I: Chemical Composition Requirements (EN 10219)

The following table details the maximum elemental concentrations permitted by EN 10219, ensuring both the required strength and the critical weldability profile for sections with a nominal thickness ($\text{t}$) less than or equal to $16\text{mm}$ (limits vary slightly for thicker sections).

| Element (Max %) | S235JR | S355JR | S355J0H | S355J2H |

| Carbon ($\text{C}$) | $0.17$ | $0.20$ | $0.20$ | $0.20$ |

| Silicon ($\text{Si}$) | – | $0.55$ | $0.55$ | $0.55$ |

| Manganese ($\text{Mn}$) | $1.40$ | $1.50$ | $1.50$ | $1.60$ |

| Phosphorus ($\text{P}$) | $0.040$ | $0.040$ | $0.035$ | $0.035$ |

| Sulfur ($\text{S}$) | $0.040$ | $0.040$ | $0.035$ | $0.035$ |

| Copper ($\text{Cu}$) | $0.55$ | $0.55$ | $0.55$ | $0.55$ |

| Nitrogen ($\text{N}$) | $0.009$ | $0.009$ | $0.009$ | $0.009$ |

| CEV (Max) | $0.35$ | $0.45$ | $0.45$ | $0.45$ |

Note: For $\text{t} > 16\text{mm}$, the maximum $\text{C}$ and $\text{CEV}$ limits generally increase slightly for all grades, acknowledging the increased difficulty in achieving a consistent microstructure in thicker material.

The table reveals the clear material strategy: S235JR is a basic, lower-carbon steel with a lower $\text{CEV}$. The S355 grades achieve their strength primarily through an increase in allowed $\text{Mn}$ (up to $1.60\%$) and the introduction of $\text{Si}$ control (a deoxidizer and strengthener), all while maintaining controlled $\text{C}$ limits. The refinement from S355JR to S355J0H and S355J2H is subtle but metallurgically significant, evidenced by the tighter maximum limits on the detrimental $\text{P}$ and $\text{S}$, which directly ensures the higher guaranteed low-temperature impact properties mandated by the $\text{J0}$ and $\text{J2}$ classifications.

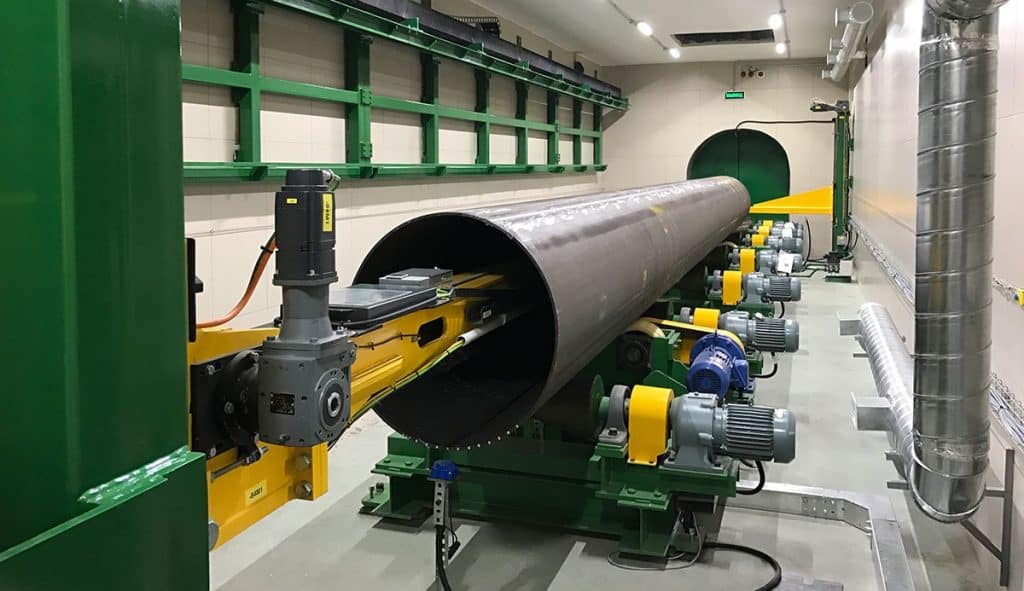

Cold Forming and the Mechanical Consequence: Stress, Strength, and Ductility

The defining feature of EN 10219 products is the method of manufacture: cold forming. The pipe, or hollow section, is typically formed from hot-rolled steel strip or plate that is first longitudinally welded (often using the Electric Resistance Welding ($\text{ERW}$) or Submerged Arc Welding ($\text{SAW}$) process) and then passed through forming rolls at ambient temperature. This process contrasts sharply with hot-formed sections (EN 10210), which are formed at high temperatures, usually above the steel’s recrystallization temperature.

Cold forming induces several crucial metallurgical and mechanical changes:

-

Work Hardening: The plastic deformation during forming causes dislocation motion and multiplication within the steel’s crystal lattice. This work hardening significantly increases the material’s yield strength and, to a lesser extent, its tensile strength. This increase in strength can, paradoxically, be both a benefit and a challenge. While the final pipe section might exhibit an actual yield strength significantly higher than the guaranteed minimum (e.g., $355\text{MPa}$), this increase comes at the expense of a reduction in ductility (elongation) and, potentially, a reduction in toughness, particularly if the steel plate was not sufficiently fine-grained to begin with. The EN 10219 standard accommodates this work hardening by specifying the mechanical tests be performed on a sample taken from the finished product, thereby validating the mechanical state after cold forming.

-

Residual Stress: The cold forming process leaves significant residual stresses locked into the pipe structure, primarily in the vicinity of the corners and the weld seam. These stresses are typically compressive on the outside surface and tensile on the inside surface. While these stresses do not necessarily impact the ultimate load-bearing capacity of the member under static tension or compression (due to subsequent yielding under load), they are critical in terms of fatigue performance and buckling resistance. For fatigue-critical applications, or those involving dynamic loading, the presence of high residual tensile stresses near weld toes or other geometric discontinuities can significantly accelerate crack initiation and propagation, making a detailed fatigue assessment necessary.

-

Weld Integrity: For the weld seam itself, the cold forming process subjects the weld and its $\text{HAZ}$ to plastic strain, which serves to both homogenize the localized variations in the microstructure and test the integrity of the weld. The cold working effect can be advantageous in normalizing any minor $\text{HAZ}$ microstructures but necessitates strict quality control during the initial welding phase to prevent defects that would be exacerbated during forming.

Table II: Tensile Requirements (EN 10219)

The tensile requirements are tested on samples taken from the finished hollow section and must meet the following minimums (for thickness $\text{t} \leq 16\text{mm}$):

| Grade | Minimum Yield Strength (ReH) MPa | Minimum Tensile Strength (Rm) MPa | Minimum Elongation (A) % |

| S235JR | $235$ | $360$ – $510$ | $26$ |

| S355JR | $355$ | $510$ – $680$ | $22$ |

| S355J0H | $355$ | $510$ – $680$ | $22$ |

| S355J2H | $355$ | $510$ – $680$ | $22$ |

The table confirms the core definition of the grades: S355 provides a minimum yield strength $120\text{MPa}$ higher than S235, representing a significant structural advantage in terms of material efficiency. This substantial increase in strength is traded for a modest reduction in minimum elongation, reflecting the metallurgical reality of the trade-off between strength and ductility. Critically, the standard also provides a range for the tensile strength ($\text{R}_\text{m}$), which acts as a ceiling to prevent excessive hardening and subsequent embrittlement, ensuring a reliable balance of properties for structural use.

The Toughest Challenge: Impact Energy and Low-Temperature Performance

For structural components, particularly those exposed to dynamic loads, seismic activity, or sub-zero climates, the material’s resistance to brittle fracture is often a more critical design parameter than its static yield strength. This resistance is quantified by the Charpy V-notch Impact Test, which measures the energy absorbed by a standardized specimen during fracture. The impact property designations ($\text{JR}$, $\text{J0}$, $\text{J2}$) are the engineer’s assurance that the pipe will not fail catastrophically in a brittle manner at the specified minimum service temperature.

The underlying metallurgical principle governing this performance is the Ductile-to-Brittle Transition Temperature ($\text{DBTT}$). All ferrous materials exhibit a change in fracture mode from ductile (high energy absorption, significant plastic deformation) at high temperatures to brittle (low energy absorption, fast crack propagation) at low temperatures. The goal of material specification, particularly for $\text{J0}$ and $\text{J2}$ grades, is to ensure that the material’s $\text{DBTT}$ is well below the lowest predicted service temperature.

The transition from S355JR to S355J2H is a clear progression of fracture control:

-

S355JR: Guarantees $27\text{J}$ at $\mathbf{+20^\circ\text{C}}$. This is suitable for general construction in temperate environments where service temperatures rarely drop significantly below freezing.

-

S355J0H: Guarantees $27\text{J}$ at $\mathbf{0^\circ\text{C}}$. This provides a slightly greater margin, suitable for structures exposed to freezing conditions but not subject to extreme cold.

-

S355J2H: Guarantees $27\text{J}$ at $\mathbf{-20^\circ\text{C}}$. This grade is essential for applications in colder regions, high-altitude installations, or structures subject to shock loading where a low $\text{DBTT}$ is vital. The achievement of this property at $-20^\circ\text{C}$ is a direct consequence of the more stringent chemical controls (lower $\text{P}$ and $\text{S}$) and the requirement for a fully killed steel (i.e., fully deoxidized) with a fine grain structure, often achieved through $\text{TMCP}$ and aluminium grain refinement. Fine grain size is the most effective way to lower the $\text{DBTT}$ and enhance toughness without sacrificing strength.

Table III: Impact Energy Requirements (EN 10219)

The following minimum average impact energy values ($\text{J}$) are required for longitudinal specimens taken from the finished product.

| Grade | Test Temperature (\text{^\circ\text{C}}) | Minimum Impact Energy (J) |

| S235JR | $+20$ | $27$ |

| S355JR | $+20$ | $27$ |

| S355J0H | $0$ | $27$ |

| S355J2H | $-20$ | $27$ |

The use of a standard $27\text{J}$ value is significant, as it is considered the minimum energy absorption level that generally corresponds to a shift to fully ductile (shear) fracture behavior, ensuring that the material has sufficient reserve capacity to absorb localized energy without immediate catastrophic failure. The requirement that this energy level must be maintained at a specific low temperature provides the fundamental structural reliability for cold-weather applications.

Heat Treatment and Condition of Supply: The Impact of Cold Work

One of the defining aspects of EN 10219 structural pipe is the standard’s general approach to heat treatment. Unlike pressure vessel or alloy steel standards that often mandate a final normalizing or quenching/tempering treatment, the $\text{S235}$ and $\text{S355}$ grades under EN 10219 are typically supplied in the as-formed condition (i.e., without post-forming heat treatment). The mechanical properties detailed in the tables are guaranteed in this state, relying heavily on the initial condition of the steel strip or plate used for forming (which may have been normalized or $\text{TMCP}$-processed by the steel mill).

Heat Treatment Requirements (EN 10219)

| Grade | Condition of Supply | Primary Technical Purpose |

| S235JR | As-formed (Cold Finished) | Relies on the inherent properties of the low-carbon, unalloyed base material. |

| S355JR | As-formed (Cold Finished) | Relies on the base material’s condition (often $\text{TMCP}$ or normalized) and the effect of work hardening. |

| S355J0H | As-formed (Cold Finished) | Relies on controlled composition and fine-grain structure to guarantee $0^\circ\text{C}$ toughness. |

| S355J2H | As-formed (Cold Finished) | Relies on controlled composition and fine-grain structure to guarantee $-20^\circ\text{C}$ toughness. |

The fact that no post-forming heat treatment is generally required is a key element in the economic viability of these products. A full-scale post-weld or post-form heat treatment (like stress-relieving or normalizing) for a large structural pipe would add significant cost and complexity.

However, the cold-formed state carries an important technical caveat: the presence of high residual stresses mentioned earlier. While not a failure mode in itself, a fabricator might elect to perform a stress-relieving heat treatment (typically at $550^\circ\text{C}$ to $600^\circ\text{C}$) after complex welding or fabrication, particularly for components intended for extremely high fatigue service or those with tight dimensional tolerance requirements. This elective treatment must be approached with caution; while it reduces residual stresses and restores a small amount of ductility, the fabricator must ensure that the treatment does not negatively affect the impact properties guaranteed by the $\text{J0}$ or $\text{J2}$ grades. Prolonged exposure to temperatures near $600^\circ\text{C}$ could, for instance, cause micro-alloy precipitates ($\text{Nb}/\text{V}$ carbides/nitrides) to coarsen, leading to a slight loss of strength and potential degradation of toughness, though this effect is generally minor for the service temperatures contemplated by this standard. The critical takeaway is that the base properties are guaranteed in the as-formed, non-heat-treated state, placing the responsibility on the steel mill to use pre-processed material (plate/coil) that already possesses the necessary fine-grain structure to withstand the subsequent cold work and meet the final $\text{J}$ toughness requirements.

Welding and Fabrication: Practical Engineering Considerations

The inherent structural efficiency of using hollow sections (HSS) is often realized in complex truss and space frame structures, which require extensive welding of sections together, often involving intricate joints where one pipe is contoured to fit the profile of another ($\text{T}$, $\text{K}$, $\text{Y}$ joints). The weldability profile, governed by the $\text{CEV}$ (Table I), is therefore paramount. The low $\text{CEV}$ values for EN 10219 pipe mean they are classified as having good weldability and can generally be welded using standard processes (e.g., Shielded Metal Arc Welding ($\text{SMAW}$), Gas Metal Arc Welding ($\text{GMAW}$), or Flux-Cored Arc Welding ($\text{FCAW}$)) with minimal or no preheating, provided the section thickness is moderate and the ambient conditions are controlled.

The primary welding consideration for these structural steels is the avoidance of Cold Cracking (or hydrogen-induced cracking) in the $\text{HAZ}$. This type of cracking occurs in susceptible microstructures (hard, martensitic-like structures formed in the $\text{HAZ}$), in the presence of tensile stress (residual or applied), and, critically, in the presence of diffusible hydrogen. The low $\text{CEV}$ of the $\text{S355}$ grades minimizes the hardenability (the formation of susceptible microstructures), while the use of low-hydrogen consumables (electrode coatings or flux) and, if necessary, minimal preheating ($50^\circ\text{C}$ to $100^\circ\text{C}$) manages the hydrogen content, ensuring a crack-free joint.

Another crucial fabrication factor, unique to HSS, is the design consideration for Fatigue at welded joints. The complexity of tubular joints results in highly localized stress concentrations ($\text{SCF}$) at the welds. For structures subjected to cyclic loading (e.g., bridges, offshore structures, cranes), the fatigue life is often the governing design criterion, overriding static strength. The high residual tensile stresses locked into the material near the weld seam due to cold forming can exacerbate this issue. Consequently, welding procedures and joint details must be carefully specified according to relevant fatigue standards (such as Eurocode 3, Part 1-9) which mandate specific joint categories and detail classes to ensure adequate service life, a consideration that is heavily influenced by the pipe’s initial cold-formed state.

Applications and Conclusion: The Pillars of Modern Construction

The EN 10219 structural steel pipes, from the foundational S235JR to the premium S355J2H, form the backbone of light-to-heavy structural engineering projects, chosen for their ideal combination of strength, cost-effectiveness, and ease of fabrication. The meticulous standardization of their chemical composition, mechanical performance, and fracture toughness ensures that they meet the rigorous demands of safety and durability across diverse environments.

S235JR pipes are generally employed in non-primary structural elements, railings, scaffolding, and light framework where strength is less critical than cost and formability. S355JR represents the industry’s default high-strength structural grade, suitable for most column, beam, and truss applications in temperate climates. The S355J0H and, critically, S355J2H pipes are indispensable for major infrastructure projects where low-temperature reliability is paramount, including:

-

Bridge Structures: Especially in regions prone to severe winters, where guaranteed fracture toughness at $-20^\circ\text{C}$ is a non-negotiable safety factor.

-

Offshore and Maritime Structures: Including jetties, piers, and small-to-medium offshore jackets, where exposure to cold seawater and wave action dictates a high degree of toughness.

-

Dynamic and Seismic Structures: Such as transmission towers, crane booms, and buildings in high-seismic zones, where the material must possess the reserve ductility and toughness to absorb energy under severe strain rates without brittle failure.

In summary, the technical success of EN 10219 pipe relies on a deeply integrated relationship between the chemistry (controlled by $\text{CEV}$ for weldability and $\text{P}/\text{S}$ for toughness), the manufacturing process (cold forming for efficiency and work-hardening), and the final mechanical guarantees (yield strength and low-temperature impact energy). The progression from S235 to S355J2H is an engineering-driven pathway, providing a graded spectrum of performance that allows designers to precisely select the most efficient and safe material for any given structural task. The inherent structural efficiency of the hollow section form, combined with the excellent weldability and guaranteed toughness of these $\text{EN}$ grades, ensures their continued preeminence as the material of choice for the world’s most vital structural works.