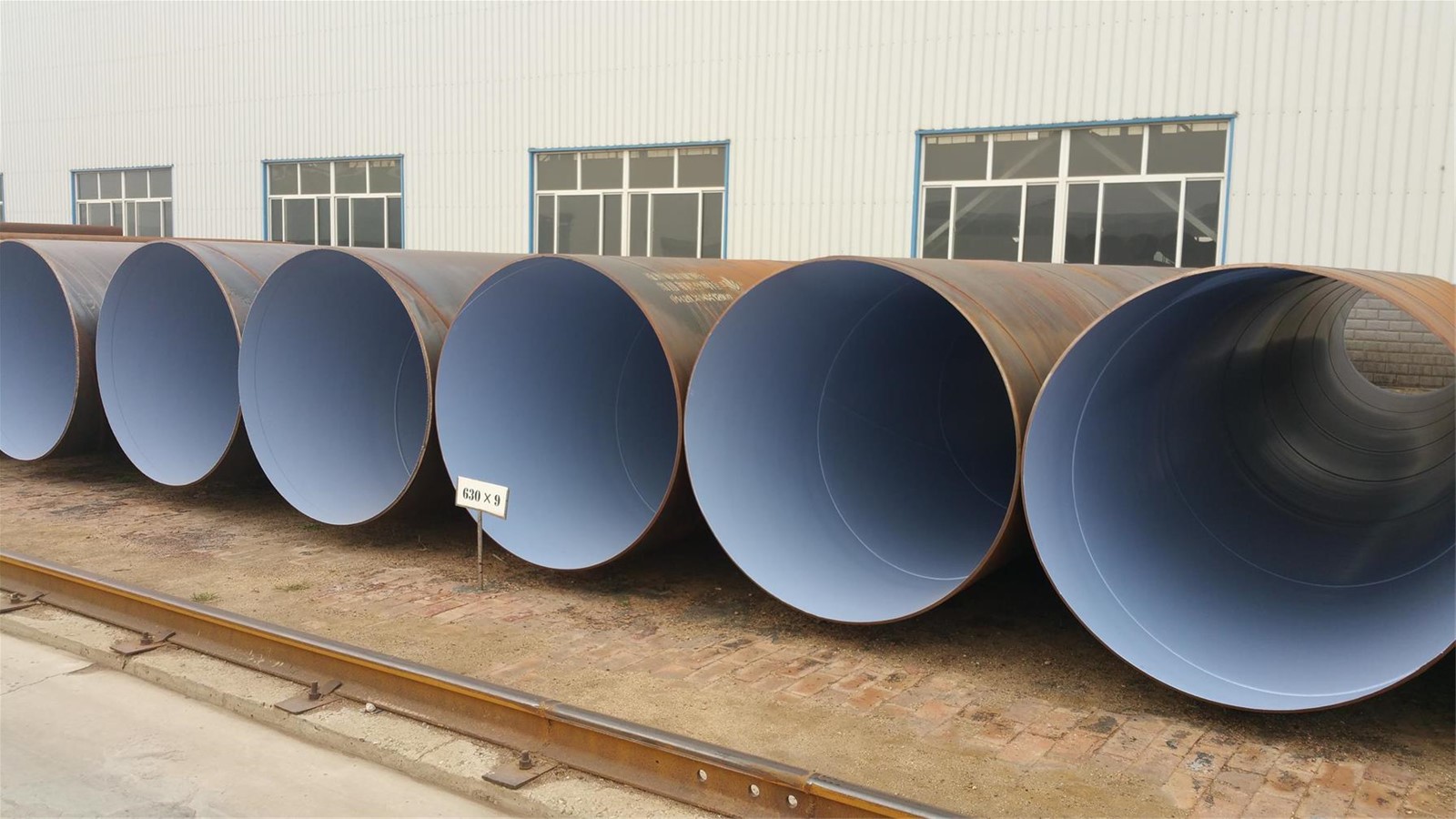

API 5L Carbon Steel SSAW Pipe

The API 5L Carbon Steel SSAW Pipe is a highly specialized piece of engineered infrastructure, a material solution fundamentally defined not by simple dimensional constraint or utility-grade corrosion protection, but by the relentless pursuit of high strength, reliable weld integrity, and exceptional fracture toughness, all necessary to ensure the safe, uninterrupted, and high-pressure conveyance of hydrocarbons, natural gas, or dense fluid slurries across vast geological and environmental landscapes. Unlike the familiar, generalized applications of utility piping, the $\text{API 5L}$ specification elevates the pipe to a critical, risk-intensive pressure vessel component, demanding compliance with an internationally recognized standard that mandates stringent metallurgical controls and exacting quality assurance protocols far exceeding those found in standard commercial piping. The unique SSAW (Spiral Submerged Arc Welded) manufacturing methodology, a technical choice driven primarily by the economic efficiency of producing large-diameter pipe from continuous steel coils, introduces its own set of critical engineering considerations related to weld geometry, mechanical anisotropy, and defect detection that must be meticulously scrutinized within the context of the operational stresses imposed on a long-distance pipeline.

The starting point for this deep technical analysis is the API 5L standard itself, which defines a spectrum of $\text{HSLA}$ (High-Strength Low-Alloy) carbon steel grades, ranging from the fundamental $\text{Grade B}$ up through the ultra-high strength grades like $\text{X80}$ and beyond, where the “$\text{X}$” denotes the minimum specified yield strength ($\text{SMYS}$) in thousands of psi. For a common high-pressure line pipe, grades such as X52 or X65 are typical, requiring the base steel plate to be manufactured using sophisticated thermo-mechanical processing, such as TMCP (Thermo-Mechanically Controlled Processed) rolling, a technique that simultaneously rolls and cools the steel to refine the grain structure, producing a fine $\text{ferrite-pearlite}$ microstructure with superior strength and ductility compared to conventionally rolled steel. This base metal must satisfy an extremely detailed set of Chemical Composition requirements, which are controlled not just by percentage weight but by calculated parameters like the Carbon Equivalent ($\text{CEq}$) and the Parameter Critical for Cold Cracking ($\text{Pcm}$). These indices are crucial technical metrics used to predict the steel’s susceptibility to hydrogen-induced cold cracking during and after the welding process, where lower $\text{CEq}$ values are specifically targeted through the controlled use of micro-alloying elements—such as niobium ($\text{Nb}$), vanadium ($\text{V}$), and titanium ($\text{Ti}$)—which manage grain size and precipitate strengthening without adding excessive carbon, thereby balancing high strength with the non-negotiable requirement for field weldability under often harsh environmental conditions.

The distinguishing manufacturing feature is the SSAW (Spiral Submerged Arc Welded) process, a production method that fundamentally differs from the $\text{LSAW}$ (Longitudinal Submerged Arc Welded) or $\text{SMLS}$ (Seamless) alternatives by forming the pipe from a strip of coil steel that is spirally wrapped and simultaneously welded both internally and externally using the high-energy, high-deposition **Submerged Arc Welding ($\text{SAW}$) ** technique. This spiral geometry offers the profound economic advantage of producing pipes of very large diameter (often exceeding $\text{NPS 60}$) from narrower, more readily available steel coils, maximizing material utilization and production efficiency. However, the $\text{SSAW}$ method introduces a unique set of technical constraints, primarily related to the weld seam geometry. The spiral weld path intersects the principal stress axes of the pipe at an angle—typically between $30^{\circ}$ and $70^{\circ}$ to the pipe axis—a critical factor because the pipe’s hoop stress (the primary circumferential stress from internal pressure) and the longitudinal stress (from thermal expansion and external loading) are no longer perpendicular to the weld line, as they are in $\text{LSAW}$ pipe. This angular path means the weld is continuously subjected to a complex combination of tensile and shear stresses, demanding exceptional confidence in the homogeneity and defect-free nature of the weld fusion zone, which is metallurgically more complex than the parent material due to the high heat input and solidification microstructure of the $\text{SAW}$ process.

The rigorous Tensile Requirements mandated by $\text{API 5L}$ ensure that the final product, inclusive of the spiral weld seam, meets the specified yield and tensile strength minimums ($\text{SMYS}$ and $\text{SMTS}$). However, for $\text{SSAW}$ pipe, the most critical mechanical testing often revolves around Fracture Toughness, particularly in pipelines intended for low-temperature service or those operating in arctic or deepwater environments where the risk of rapid, brittle crack propagation is paramount. This necessitates compliance with strict Charpy V-Notch (CVN) Impact Testing requirements, which involve measuring the energy absorbed by specimens taken from the pipe body and, crucially, from the HAZ (Heat-Affected Zone) of the spiral weld at specified minimum design temperatures, often below $0^{\circ}\text{C}$. The objective is to ensure that the steel exhibits a Ductile-Brittle Transition Temperature ($\text{DBTT}$) safely below the lowest anticipated operating temperature, guaranteeing that any nascent crack initiation will lead to tough, ductile failure (slow, predictable tear) rather than catastrophic brittle fracture (rapid, unpredictable cleavage) that can propagate for miles down the pipeline, a core technical distinction from utility pipe where CVN requirements are typically non-existent. .

The integrity of the spiral weld seam, which runs the entire length of the pipe, is secured through comprehensive Non-Destructive Testing ($\text{NDT}$) protocols mandated by $\text{API 5L}$. Unlike simpler pipe where spot checks might suffice, $\text{SSAW}$ requires near-continuous inspection. This typically involves $100\%$ Automatic Ultrasonic Testing ($\text{AUT}$) of the weld volume, often supplemented by **Radiographic Testing ($\text{X-ray}$ or $\text{Gamma Ray}$) ** to detect internal volumetric defects like porosity or inclusions that $\text{UT}$ might miss, and a final visual inspection of the weld beads for surface discontinuities. The sheer geometric complexity of the spiral weld path requires sophisticated $\text{UT}$ transducer arrays to ensure complete coverage, capable of detecting and sizing critically oriented defects—such as lack of fusion or embedded planar flaws—that are highly detrimental to the pipe’s fatigue life and burst strength. The technical acceptance criteria for these defects are extremely stringent, defined by the $\text{API 5L}$ annexes, reflecting the high consequences of failure in high-pressure line pipe service, where the volumetric contents (e.g., natural gas) represent both an immense economic loss and a significant environmental and public safety hazard.

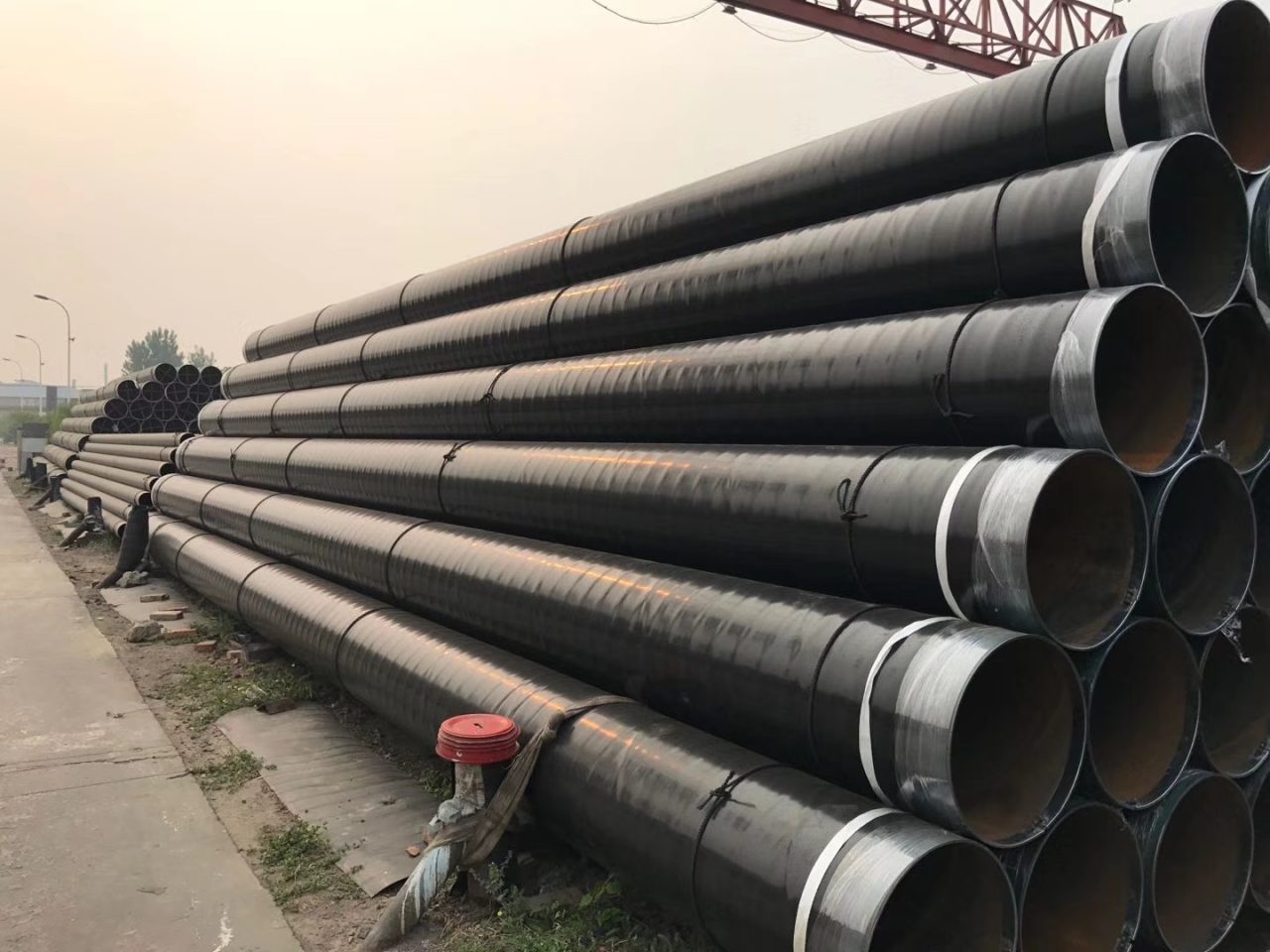

Beyond structural integrity, the performance of the $\text{API 5L SSAW}$ pipe is profoundly affected by the potential for Corrosion Failure Mechanisms, which necessitates the application of advanced external and internal coatings, as the bare carbon steel pipe itself offers no inherent long-term protection. External corrosion is combatted through factory-applied, multi-layer systems—most commonly **Fusion Bond Epoxy ($\text{FBE}$) ** or **3-Layer Polyethylene ($\text{3LPE}$) **—which are applied after the pipe is grit-blasted to near-white metal standard, creating a high-adhesion dielectric barrier that insulates the pipe from the corrosive soil environment. Internally, the high-strength steel grades are susceptible to Stress Corrosion Cracking ($\text{SCC}$), Sulfide Stress Cracking ($\text{SSC}$), and Hydrogen Induced Cracking ($\text{HIC}$), especially when conveying “sour” gas ($\text{H}_2\text{S}$) or high-$\text{CO}_2$ fluids. Therefore, the specification often requires the steel to be qualified as HIC-resistant, demanding specialized low-sulfur content and inclusion shape control through calcium treatment, a costly metallurgical enhancement that is non-negotiable for service in aggressive environments, reinforcing the technical distinction between this specialized line pipe and standard utility grades.

Finally, the ultimate verification of the $\text{API 5L SSAW}$ pipe’s structural capacity is the mandatory, non-destructive Hydrostatic Test, wherein the pipe is pressurized in a test rig to a minimum pressure (typically $1.25$ to $1.5$ times the maximum allowable operating pressure, or $\text{MAOP}$) held for a specified duration. This test serves as a crucial mechanical proof, verifying the pipe’s elastic strength and the integrity of the spiral weld under simulated operating conditions. The rigorous nature of this testing, combined with the stringent $\text{API 5L}$ requirements for material traceability, documentation, and the application of complex corrosion protection systems, ensures that the API 5L Carbon Steel SSAW Pipe is not just a tube, but a highly engineered, certified pressure containment vessel designed for predictable performance and extended service life under some of the most demanding environmental and operational conditions found in industrial infrastructure. The table below consolidates the critical technical parameters derived from this deep analysis.

Structured Technical Specification Data: API 5L Carbon Steel SSAW Pipe

| Category | Technical Specification | Typical Requirements & Standards | Technical Significance for High-Pressure Line Pipe |

| Material Grade | API 5L High-Strength Low-Alloy (HSLA) | Common Grades: $\text{X52, X65, X70}$. Requires control of $\text{Nb, V, Ti}$ micro-alloying elements. | Yield strength ($\text{SMYS}$) must meet high minima (e.g., $\text{X65}$ requires $65,000 \text{ psi}$) for safe, high-$\text{MAOP}$ operation. |

| Manufacturing Method | SSAW (Spiral Submerged Arc Welded) | Pipe formed helically from strip steel; internal and external weld passes using the $\text{SAW}$ process. | Economical for large diameters ($\text{NPS 24+}$). Weld path is oblique to stress axes, demanding high weld quality. |

| Governing Standard | API Specification 5L | Defines material grades, dimensions, chemical limits ($\text{CEq}$), $\text{NDT}$ requirements, and testing procedures (e.g., flattening, impact tests). | Global standard for line pipe integrity, focusing on strength, fracture toughness, and safety in gas/oil transmission. |

| Chemical Composition | Controlled $\text{CEq}$ and $\text{Pcm}$ | $\text{C} \le 0.23\%$. Carbon Equivalent ($\text{CEq}$) $\le 0.43$. $\text{S}$ and $\text{P}$ tightly controlled ($\le 0.015\%$). | Low $\text{CEq}$ ensures field weldability and minimizes susceptibility to hydrogen-induced cold cracking ($\text{HIC}$). |

| Heat Treatment Req. | As-Welded / Normalized / Quenched & Tempered (Q&T) | Varies by grade; $\text{TMCP}$ (Thermo-Mechanically Controlled Processing) is common for plates. Weld seam may require heat treatment. | $\text{TMCP}$ refines microstructure for superior strength and toughness, essential for low $\text{DBTT}$. |

| Tensile Requirements | SMYS & SMTS | $\text{API 5L Grade X65}$ example: $\text{SMYS} = 65,000 \text{ psi}$. $\text{SMTS}$ (Min. Tensile) $= 77,000 \text{ psi}$. | Confirms ability to withstand design pressures and external loads without yielding, with sufficient safety margin. |

| Toughness Requirements | Charpy V-Notch (CVN) | Min. absorbed energy required (e.g., $40 \text{ Joules}$) at specific testing temperatures (e.g., $0^{\circ}\text{C}$ or $-20^{\circ}\text{C}$). | Guarantees resistance to rapid brittle fracture propagation, a critical failure mode in high-pressure line pipe. |

| Quality Control (NDT) | $100\%$ Weld Inspection | Automatic Ultrasonic Testing ($\text{AUT}$) of the entire spiral weld, often supplemented by $\text{X-ray}$ for volumetric defects. | Ensures the spiral weld seam is free of planar defects (lack of fusion/penetration) that compromise integrity. |

| Application | High-Pressure Line Pipe | Transport of oil, natural gas, refined petroleum products, and high-pressure fluid slurries over long distances. | Optimized for continuous, high-volume, high-pressure service demanding maximum reliability and safety. |

| Tolerance of $\text{OD}$ and $\text{WT}$ | API 5L Dimensional Tolerances | $\text{OD}$ tolerance is tight (e.g., $\pm 0.5\%$). $\text{WT}$ tolerance is typically tight ($\pm 10\%$) due to large size. | Tight control is necessary for consistent fit-up during field welding and ensuring accurate internal volume and pressure capacity. |

One of the most critical, yet often subtle, technical consequences of the spiral weld path is the resulting anisotropy of mechanical properties and its implication for stress distribution under service load. Because the weld seam runs at an acute angle (typically $30^{\circ}$ to $70^{\circ}$) to the pipe’s axis, the weld material and its associated HAZ (Heat-Affected Zone), which are metallurgically distinct and potentially less tough than the parent $\text{TMCP}$ steel body, are simultaneously stressed by both the high hoop stress (circumferential tension caused by internal pressure, the pipe’s maximum stress component) and the longitudinal stress (axial tension caused by thermal expansion, bending, or Poisson effects). This complex, bi-axial loading on the weld seam, unlike the primary hoop-stress loading experienced by longitudinal welds, necessitates that the $\text{SAW}$ process parameters—including heat input, wire chemistry, and flux composition—be meticulously controlled to ensure that the weld metal deposited maintains mechanical properties that are sufficiently robust to withstand this combined stress state, often requiring overmatching strength relative to the parent metal, alongside superior low-temperature impact toughness, a technical balance that demands continuous and sophisticated monitoring of the welding process variables. The consequence of failure here is non-trivial; a defect in the spiral weld, subjected to this complex stress field, risks the propagation of a fracture along the weld line, a failure mode that is unique to the $\text{SSAW}$ geometry and requires comprehensive theoretical modeling during the design phase to predict critical defect sizes and acceptable operating pressures.

Furthermore, the logistical and financial implications of the $\text{SSAW}$ geometry extend directly into the high-tech realm of pipeline operation and maintenance, specifically impacting In-Line Inspection (ILI), often performed by sophisticated electronic devices known as $\text{PIGs}$ (Pipeline Inspection Gauges). These $\text{PIGs}$ utilize technologies like **Magnetic Flux Leakage ($\text{MFL}$) ** or **Ultrasonic Testing ($\text{UT}$) ** to scan the pipe wall for corrosion, cracks, or manufacturing defects while traveling hundreds of miles inside the pipeline. The geometry of the $\text{SSAW}$ pipe, with its continuous, helical weld bead running along the inner wall surface, presents a unique challenge to the $\text{ILI}$ tools, as the weld profile can interfere with the sensor arrays, potentially leading to increased noise or false indications, demanding specific software algorithms and hardware adjustments to accurately interpret data recorded along the spiral path, adding a layer of complexity and cost to the routine integrity management of the pipeline network. Conversely, the $\text{SSAW}$ process itself, by utilizing coiled steel, benefits immensely from the metallurgical advancements inherent in TMCP (Thermo-Mechanically Controlled Processed) steel, where the specific micro-alloying additions—notably Niobium ($\text{Nb}$), Vanadium ($\text{V}$), and Titanium ($\text{Ti}$)—play a profound role in achieving the required high strength and toughness. These elements are not simple alloying agents; they are metallurgical tools. Niobium, for example, is instrumental in grain refinement and precipitation strengthening, forming fine $\text{Nb}$-carbides and nitrides that pin the grain boundaries, preventing recrystallization during the $\text{TMCP}$ cooling phase, resulting in an exceptionally fine-grained, high-strength $\text{ferrite}$ structure that simultaneously enhances both the $\text{SMYS}$ and the low-temperature fracture toughness, a technical feat essential for the safe use of $\text{API 5L}$ pipe grades like $\text{X65}$ and above in cold weather environments.

The ultimate verification of the pipe’s fitness for service, transcending all preceding inspection and testing, is the mandatory, non-destructive Hydrostatic Test, a critical protocol defined by $\text{API 5L}$ where the pipe is subjected to an internal pressure significantly higher than its maximum anticipated operating pressure ($\text{MAOP}$), typically ranging from $1.25$ to $1.5$ times the $\text{MAOP}$. The purpose of this test extends beyond merely checking for leaks; it serves as a crucial proof test, plastically deforming the material and effectively screening out pipe segments that contain flaws near the critical failure size, which would otherwise burst during the test rather than in service. The physics behind this involves pushing the pipe material into the plastic region (where stress exceeds the $\text{SMYS}$), a process that, counter-intuitively, improves the pipe’s long-term integrity by blunting existing small cracks and subjecting the entire SSAW weld seam to the maximum design stress, providing a definitive, full-scale verification of the pipe’s structural capacity. Furthermore, this plastic deformation induces a phenomenon known as the Bauschinger Effect on the stress-strain curve, subtly altering the material’s properties in a way that can improve the pipe’s fatigue resistance under subsequent operational pressure cycles, making the Hydrostatic Test not just a quality control check but an active enhancement of the pipe’s long-term structural resilience.

The inherent susceptibility of the base carbon steel to corrosion, especially when buried and subjected to aggressive soil electrolytes, necessitates that the final $\text{API 5L SSAW}$ pipe specification includes the application of robust external corrosion protection systems, a technical requirement that fundamentally differs from the intrinsic $\text{HDG}$ protection used for utility pipe. For buried line pipe, the primary defense is a dielectric barrier coating, such as **3-Layer Polyethylene ($\text{3LPE}$) ** or **Fusion Bond Epoxy ($\text{FBE}$) **, applied to the pipe exterior after meticulous abrasive blast cleaning. The $\text{3LPE}$ system, a complex multi-stage coating involving an initial $\text{FBE}$ primer for exceptional adhesion, a copolymer adhesive, and a final polyethylene outer layer for mechanical protection, is specified because it provides a highly resistant barrier against external moisture and soil contaminants, maintaining a high dielectric strength which is absolutely necessary for the effective functioning of the supplementary **Cathodic Protection ($\text{CP}$) ** system. The $\text{CP}$ system, which is required alongside the coating for long-term protection, relies on the coating’s integrity to limit the current demand, ensuring that the zinc or magnesium sacrificial anodes (or impressed current systems) can effectively protect the entire pipeline against galvanic corrosion over its intended service life, a crucial engineering integration of material science and electrochemistry that guarantees the 50-year-plus operational lifespan expected of modern transmission pipelines.

The operational reality of the API 5L Carbon Steel SSAW Pipe is thus a highly demanding environment where every component, from the $\text{TMCP}$ steel’s micro-alloying content to the angle of the spiral weld and the $\text{NDT}$ certification, must work in seamless concert to contain enormous pressure safely. The pipe’s $\text{API 5L}$ specification transcends mere material selection; it defines an entire quality management system, ensuring that the stringent requirements for Chemical Composition ($\text{CEq}$ control for weldability), Tensile Requirements ($\text{SMYS}$ for pressure capacity), and Toughness Requirements ($\text{CVN}$ for fracture safety) are verified and documented at every stage of production, creating an auditable record of integrity essential for critical infrastructure projects where failure is simply not an option. The deep-seated technical constraints of the $\text{SSAW}$ process, coupled with the uncompromising demands of the $\text{API 5L}$ standard, result in a highly engineered product that sits at the zenith of large-diameter fluid conveyance technology.